After rediscovering herself through meditation, retired pro basketball star Valerie Still has forged a new legacy in Palmyra

Valerie Still is the all-time leading scorer and rebounder for University of Kentucky women’s basketball, an American Basketball League champion and one of the first players to join the WNBA. In December, the Camden native added Naismith Memorial Hall of Fame nominee to the long list of prestigious classifiers she has accumulated over the years, but right now, she’s thinking about her shoes.

On the day she was scheduled to defend the dissertation she spent years working on at Ohio State University, Still received word that her mother was in the hospital and flew to New Jersey to find her on life support. When she died a few hours after being taken off the machines, Still found herself in need of proper attire for the burial.

“I just realized that today I put on the pair of shoes I had to buy for her funeral,” she said, recalling that world-shattering event in 2010. “It’s ironic that I’m back in Palmyra. My mom was the most important person in my life.”

She was left with little choice but to pack up and move with her son in 2012 when the house she bought her mother in the early 1990s failed to sell. Reeling from a turbulent divorce and suddenly stuck in an unfamiliar place without the guidance of her “best buddy,” Still said of her mother, 2014 came crashing in as her son departed for the U.S. Naval Academy. She was an MVP, a television entertainer and occasional fashion model who lived and played professional basketball in Italy for 12 years. At 35, she saw another childhood dream come to fruition with the formation of a women’s National Basketball League, along with an opportunity to play for the Washington Mystics shortly before retiring in 2000. Her photo hung in the South Jersey Basketball Hall of Fame.

Those titles meant little now that she was alone, in her mother’s small New Jersey hometown, with little direction and a burden many retired pro athletes feel haunted by after they hang up their jerseys: Who am I?

Since taking up residency in Palmyra, Still filled her time by writing her memoirs and substitute teaching part-time at Camden High School, but the real work started when she began learning to accept, and later appreciate, the circumstances that brought her back to South Jersey.

“The last couple years, I kind of disconnected. I had an identity crisis because I was known as ‘the basketball player’ and then ‘mom.’ That’s how I ended up at the meditation center,” Still remembers of her arrival at Brahma Kumaris Meditation Center on Riverton Road. “The day that I got there, they were starting a foundational course, and it was centered around the premise of identity. I was trying to find mine, so it was perfect.”

The spiritual guidance Still derived from Brahma Kumaris saved her sanity. Sister Kinnari Murthy, who led the group Still stumbled upon, said she was not sure what pulled Still to the center, but invited her and the rest of the class on a journey. That journey ultimately taught Still that the temporary identities that had landed her in an existential crisis were just that: temporary.

“I was always trained to be competitive and fight the world, being impoverished and put into all these categories — female, minority — and as the ninth of 10 children, I was always fighting to get what I wanted. It came naturally to me. The hard thing was being vulnerable and letting things go,” Still said.

Once that vulnerability began to come naturally, too, Still started making waves in the Palmyra community, and she hasn’t slowed down since. Clearing her mind of wasteful thoughts allowed her innate curiosity to find its way back to her, and it brought her to the doors of Palmyra High School, which her mother adored and spoke of often. Visiting it was something she and Still were never able to do together.

That’s when she found out her mother graduated with Clarence B. Jones in 1949, Still said.

Thrilled by the discovery that her mother walked the same halls as Martin Luther King Jr.’s attorney and co-writer of the landmark “I Have a Dream” speech, Still got to digging. The subsequent correspondence Still started with Jones to find out more about her mother has not only yielded far-reaching results, but revealed to Still that her mother’s death brought her to Palmyra for a reason.

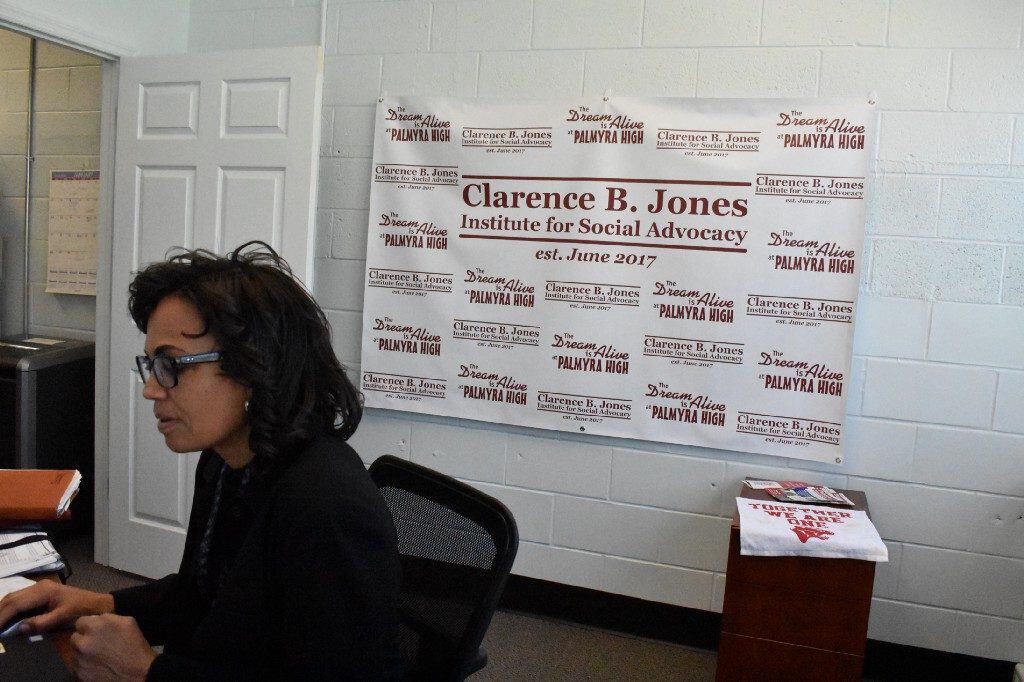

When she bought the black loafers for her mother’s funeral in 2010, she did not foresee they would carry her into a new chapter as Palmyra’s resident historian and the communications officer for the borough’s local public schools. But one conversation with Jones led to another, which led to the foundation of the Gwendolyn A. Ricketts and Clarence B. Jones scholarships in honor of Stills’ mother and the civil rights icon. Most recently, Still spearheaded and continues to oversee the Clarence B. Jones Institute for Social Advocacy, which educates students about social issues and civil rights history and provides them opportunities for service. She brought Jones back to his alma mater in June for the institute’s dedication ceremony and roundtable panel, drawing attention across New Jersey.

Whether Still knows, or cares, that her research and volunteerism in Palmyra has earned her a new legacy apart professional basketball remains to be seen. She doesn’t spend time worrying about who she is on paper anymore.

“Everything I do honors my mother,” she said. “She gave me life, and it’s her legacy that I try to carry on.”

Back at her desk at the Board of Education offices on Delaware Avenue, in between the endless tasks required of the district communications officer and leader of the CBJ Institute for Social Advocacy, the one thing Still is sure of is that somewhere, her mother is really, really enjoying what her daughter has accomplished in little Palmyra.